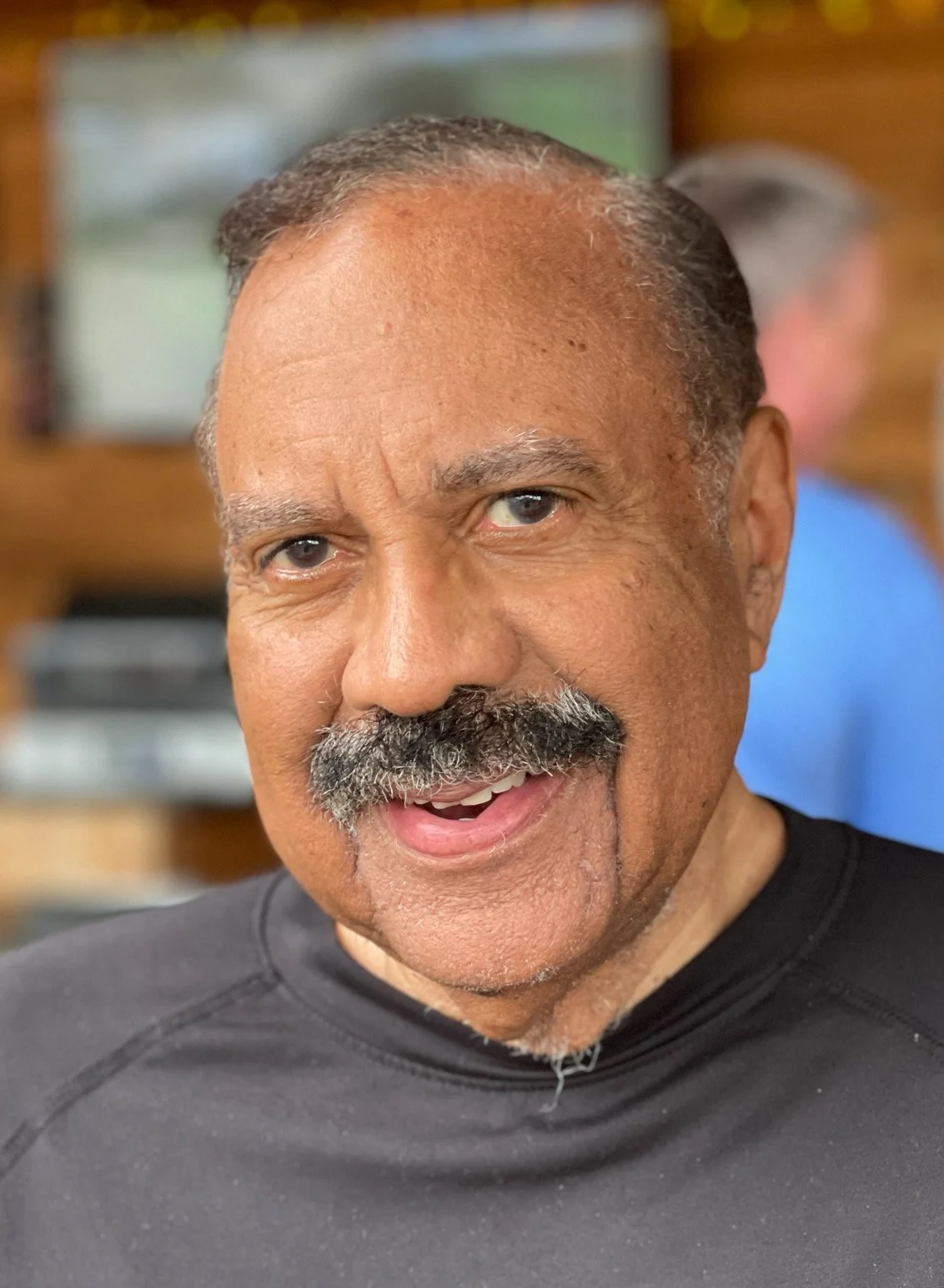

Frederick Mitchell

2025

By Tim Harmon

Growing up in Gary, Fred Mitchell had two great passions: sports and writing. Sometimes, they intertwined.

There was, for instance, the morning after his team won big and Mitchell went five-for-five, including a home run over the left-field fence. As he and his older brother assembled Sunday Post-Tribunes for their paper route, Mitchell eagerly checked the sports section for the Little League roundup, and there it was: his name in newsprint, for the first time.

It was a thrill he never forgot.

Rather than choose sports or journalism, Mitchell seemed to always find a way to pursue and succeed in both.

For a while, sports dominated. He was sports editor, then editor of the paper at Gary’s Tolleston High School. But at the same time, he was a sprinter and relay runner for the track team, second baseman on the baseball team and kicker on the football team.

The specialized skill of place-kicking was one Mitchell had taught himself after his father gave him a football at age seven.

“I'd go out in the backyard and kick from my backyard into an empty lot across the alley, over the telephone wires,” he recalled. “So, I'd kick it back and forth, back and forth, and I got pretty good.”

Later, he found an opportunity to upgrade when new carpeting arrived for their home wrapped in bamboo poles. “I stuck those in the sand in the empty lot for the uprights, and then I used my mother's clothesline for the crossbar.”

In those days, many high school football teams didn’t have designated kickers on their roster, Mitchell said. It was more customary to run for the extra points.

But one day, as Mitchell was in PE class kicking 45-yarders over a high right-field fence from second base on the school’s baseball diamond, Tolleston’s football coach was watching. On the spot, he told the 14-year-old sophomore — Mitchell had skipped a grade in elementary school — that he would be joining the varsity team.

Mitchell was courted by the Indiana University football program but ultimately decided to go to Wittenberg University, a small Ohio school with an ambitious college-division football program. In those days, there were only two tiers of college athletics, so Wittenberg competed against many schools that today are Division 1 programs.

Playing for Wittenberg, he set the college division record for most career points scored by kicking.

After graduation, Mitchell taught English and coached track and football at the Grove City, Ohio, high school, and played semipro football for the Columbus Bucks and briefly for the Chicago Heights Broncos.

However, the urge to be a writer had never left Mitchell. In 1974, he joined The Chicago Tribune as its first Black sports staffer, the beginning of a career that allowed him to fully combine his experience as a competitive athlete with his love for newspapers.

But it was here that Mitchell’s life almost took a very different path. While Mitchell was still copy editing and waiting for a beat opportunity to open up, the sports editor who had hired him and promised him good writing opportunities was sidelined to full-time column writing.

The editor’s replacement soon took Mitchell aside for a little talk and asked him to prepare to move on, saying, “I just don’t think this is going to work out.” He offered to help Mitchell get a job at a place that he might fit in better, such as The Chicago Defender, a publication that served the Black community.

“I said, ‘Why? What's the reason?’” Mitchell recalled. “He said, ‘Oh, I just got a hunch.’”

“And I said, ‘You haven't even had a chance to see me write yet,’” Mitchell recalled.

Blindsided and crushed, Mitchell decided to do something he had never done before. He went over his supervisor’s head to the paper’s editor and stated his case boldly: “There’s been no solid reason given for this.”

Within a couple of days, Mitchell said, he received a call from the editor’s office: “You’re back, you’re OK.”

Soon he was teamed with the department’s lead high school reporter. “He sort of mentored me, as you say. And we were a two-man prep department. It was a great experience for me to cover football, basketball, track, every prep sport within the city and greater Chicago.”

Today, Mitchell talks of that encounter with poorly cloaked racism without bitterness. He even notes that the editor who wanted to get rid of him later admitted that he almost made the biggest mistake of his life. “You know, if I had not said anything, spoken up, and just gone along with his ‘hunch,’ my life and career would have turned out much, much differently.”

In the ensuing 41 1/2 years on The Tribune, Fred Mitchell would excel as a writer, becoming the only staffer to have served as main beat writer for the Bulls, Cubs and Bears. He spent two decades as a columnist and wrote several books about Chicago sports legends along the way.

He has been recognized for his accomplishments on the athletic field, his work in the newsroom and service to his communities. Induction into the Indiana Journalism Hall of Fame is only the latest of many honors he has received, including induction into the American Football Association Semipro Hall of Fame, the Media Award from the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame in 2023, the Ring Lardner Award for sports writing in 2015 and, last year, induction into both the Gary Sports Hall of Fame and the Indiana Sports Hall of Fame. He’s also been honored for his service to the Muscular Dystrophy Association and Chicago’s Metropolitan Family Services.

He even has an award named for him: The Fred Mitchell Award for the top place-kicker at a non-Football Bowl Subdivision college.

Mitchell, his wife, Kimberly, and son, Cameron, live in Chicago. He still writes occasionally at fredmitchellwriter.com and teaches sports journalism as an adjunct professor at DePaul University. He tells his students no one knows what sort of platforms their work will be appearing on in the future, just as he couldn’t have foreseen the internet when he was a young sportswriter in the 1970s.

But he adds, “Now more than ever we need responsible and accurate information to debunk all this false information that’s coming out on social media.”

The young boy who cherished a newspaper report on a Little League triumph grew up to weave his sports and sports writing into a legendary career that enriched fans and readers.

“Sports and writing turned out to mesh very well in my life,” he said.